Substance Over Style

ChatGPT-4o goes Ghibli-mad

Ever since the introduction of ChatGPT, and certainly since the debut of Stable Diffusion and Midjourney, artists and writers have worried, often quite vocally, about the ability of generative AI models to produce works that mimic their creative style. And they have pressed Congress, the U.S. Copyright Office and courts to recognize artistic style as a form of intellectual property worthy of legal protection against algorithmic copycats.

The U.S. Copyright Office even took up the question as part of its study of the relationship between AI and copyright. But both the office and Congress have maintained that “style” was simply too imprecise a concept to come within the legal scope of copyright and that whatever elements do comprise it do not cross the idea/expression divide. An individual artist’s and writer’s style will also often evolve over time, making it difficult to pin down. And so the question has largely faded, at least within legal and legislative channels.

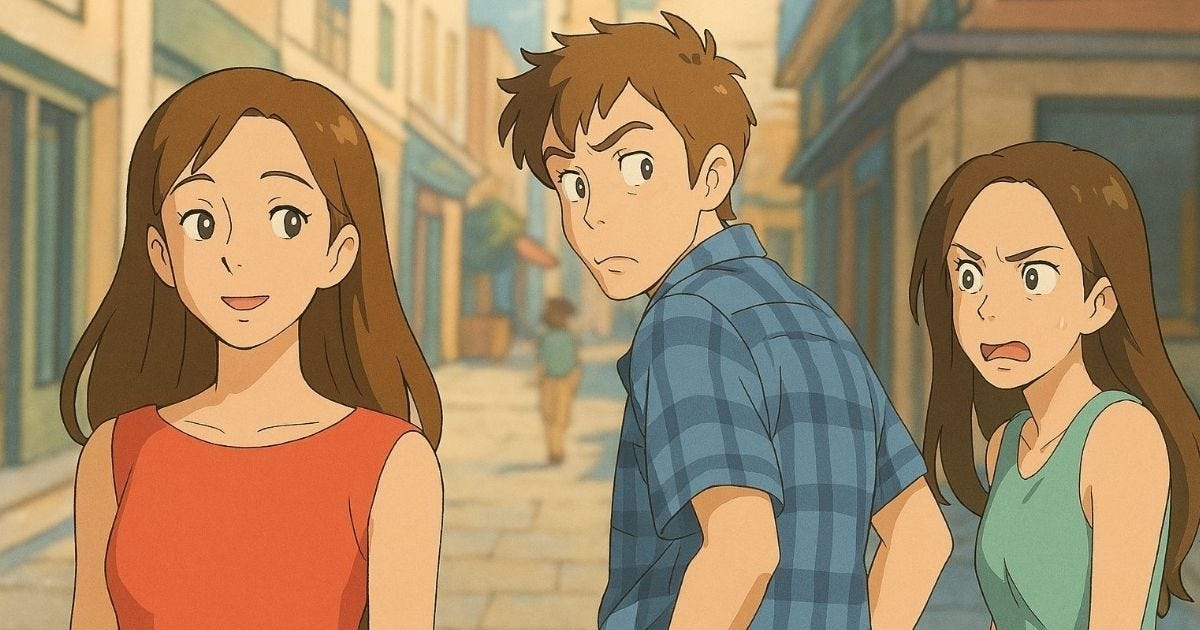

OpenAI’s introduction last week of a new image generator as part of its ChatGPT-4o has reignited the debate, however. The new feature triggered a viral mania for generating images in the distinctive style of Studio Ghibli, the studio behind animated blockbusters like “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Spirited Away,” and co-founded by the legendary Japanese artist Hayao Miyazaki. Even OpenAI CEO Sam Altman got into the act, replacing his profile picture with a Ghibli-style generated image. By Friday, however, ChatGPT users reported receiving error messages reading, "OpenAI has restrictions on generating images in the style of specific artists, including Studio Ghibli. This is due to copyright and intellectual property concerns."

As with most things AI, the question at issue in the debate is more complicated than the immediate case. For one thing, most of the discussion around the Ghibli-style meme referenced U.S. copyright law, overlooking the fact that Ghibli, which is owned by Nippon TV, is based in Japan. Any litigation that might be filed in response to the mimicry is more likely to be filed there than in the U.S.

Moreover, insofar as such litigation would likely center on the use of Ghibli movies as training inputs, as some experts have suggested, Japanese copyright law includes a fairly broad text-and-data mining exemption, including for commercial uses, which likely might-well apply. That’s not say Studio Ghibli would be barred from bringing a lawsuit in the U.S. under U.S. law. Most, if not all, of the training probably occurred here. But litigating a case in a foreign territory under foreign law is a difficult and expensive undertaking.

As of Tuesday, the Ghibli mania was still going strong on ChatGPT, and was even spreading to other animation styles, like the LEGO movies. But it’s possible, perhaps even likely, that the fad will run its course in due time, just another meme that struts and frets its hour upon the internet until the next one comes along. If the debate does outlive the meme, however, the deeper question it raises is whether copyright is the best lens through which to view l’affaire Ghibli.

Copyright, as any IP lawyer will tell you, protects original expression, not ideas, facts or concepts. Artistic style can be strongly associated with individual artists. Think, Edward Hopper’s isolated subjects, Hemingway’s spare sentences, Keith Richards’ arresting, open-tuned guitar riffs. It can even be considered, in aggregate, to be expressive. But copyright doesn’t deal in aggregates. It attaches to an individual original expression irrespective of its relationship with other, even very similar, expressions.

OpenAI also seems to draw a distinction between an individual artist’s identifiable style and a studio’s house style.

“Our goal is to give users as much creative freedom as possible. We continue to prevent generations in the style of individual living artists, but we do permit broader studio styles,” an OpenAI spokesperson said in a statement to the media.

But artistic style, like a brand, has real economic value, even if it doesn’t qualify for copyright. Brand value, in fact, can be quantified, carried as goodwill on a balance sheet. It can also be impaired, as Elon Musk’s ongoing immolation of Tesla’s brand (and share price) amply demonstrates. Deliberate impairment or dilution of a brand can even be actionable.

Some things associated with a brand, such as a trademark, can be protected as a form of intellectual property. But even a brand itself, apart from any protected indicia, is tradeable and licensable, as any McDonald’s franchisee can tell you.

Whether artistic style is substantial enough and sufficiently stable over time to warrant legal protection ultimately is a question of line-drawing and its cultural and economic costs and benefits. But it may have real economic value even without such delineation.

What Ghibli and Miyazaki are currently suffering at the hands of the ChatGPT users is more plausibly viewed as a misappropriation of that economic brand value than a copyright infringement.