Oopsie Daisy! OpenAI Deletes Discovery Data in NYTimes Lawsuit

Wrapping up the week of November 18-22

Lawyers for the New York Times and the Daily News this week sent a letter to the judge hearing their copyright infringement lawsuit against OpenAI claiming engineers at the AI company deleted data potentially pertinent to the case from its servers. OpenAI said the deletion was accidental, a claim the plaintiffs do not dispute. But the screwup has brought heightened — and to OpenAI unwelcome — attention to the data-management practices of AI developers, and to questions about whether tools in fact exist to be able to identify whose scraped data was used, and when and how, to train AI models, if someone wanted to use them.

The chain of events goes something like this: As part of court-ordered discovery in the case, OpenAI created two virtual machine “sandbox” environments the plaintiffs could use to search OpenAI’s training datasets for their own content. After that work had begun, OpenAI engineers inadvertently deleted the search results from one of those virtual machines. The engineers were able to recover the data, but the original folder structure and file names were FUBAR, breaking the chain of provenance and making the data unusable in court. The only solution available to the plaintiffs was to start from scratch and re-do 150 hours of paid work by experts and lawyers.

Meanwhile, the plaintiffs had provided OpenAI with information it would need to conduct its own search, and suggested it was best positioned to examine its own datasets. As of this week, however, plaintiffs had not received confirmation that OpenAI had undertaken such a search. Instead, counsel for the defense informed them OpenAI would “neither admit nor deny” whether Times and News content had been scraped and used in training.

The dispute’s implications for the immediate case aside, OpenAI’s Inspector Clouseau act couldn’t have come at a worse time for AI developers. California, where many AI companies including OpenAI are based, recently enacted a data transparency law (AB-2013) requiring AI developers document and disclose the sources and/owners of data used in training, a description of the types of data use, and whether they’re protected by copyright, patent or trademark.

The European Union, meanwhile, is moving along on fully implementing its AI Act, which includes strict data retention, documentation and disclosure requirements for AI developers. This week also saw it publish an updated version of its product liability directive to account for AI, among other things. The update was necessary, according to the published recitals, because, “Experience gained from applying [the existing] Directive has also shown that injured persons face difficulties obtaining compensation due to… challenges in gathering evidence to prove liability, especially in light of increasing technical and scientific complexity.”

Data governance practices at OpenAI, the poster child for generative AI, are now exposed as not up to the task. And its a fair bet that, in the race to create ever-larger and more powerful models, other developers have similarly played fast and loose with what they’re feeding into their systems. Thanks to OpenAI, they now have a big bright target on their backs for regulators and potential plaintiffs.

The exposure of OpenAI’s mishandling of training data could also prove galvanizing for the U.S. Congress — assuming it’s able to function in any sort of orderly fashion under a Trump regime — to enact federal data transparency and disclosure laws.

Finally, by wiping out the publishers’ efforts to find their content in its training datasets, OpenAI effectively has blown up its legal strategy of forcing the burden of discovery onto the plaintiffs to find the evidence to prove their case. It is now has little choice but to refuse to admit or deny whether it scraped and used the content. To admit either would be to acknowledge it in fact posses, or could create, the tools to track and attribute the data used by its models, but refuses to use them.

That leaves it trapped in the legally awkward position of appearing not to be forthcoming with the court, a situation no litigant would want to be in.

It was a costly mistake, legally. And it could get a lot costlier financially.

ICYMI

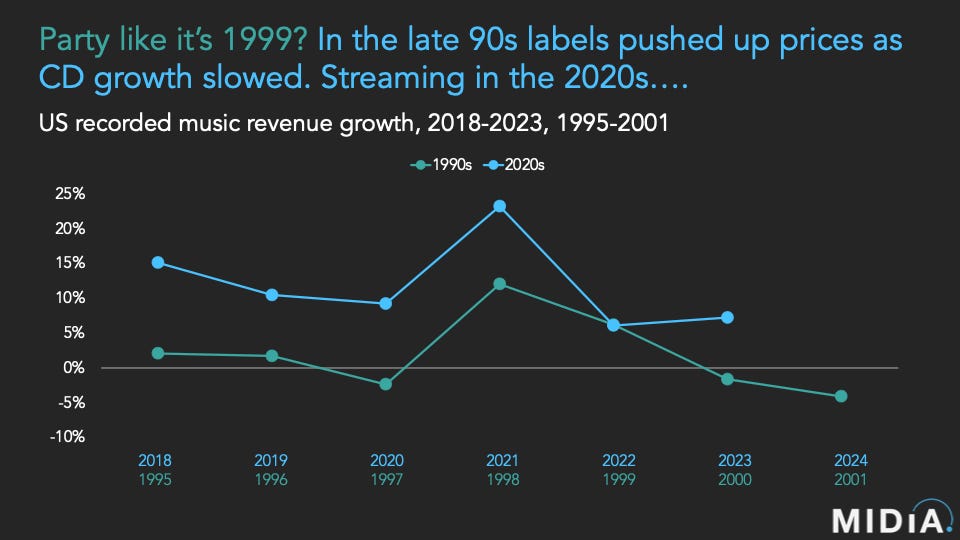

Innovator’s Dilemma Always read MIDiA Research head Mark Mulligan. His latest post analyzes Spotify’s recent earnings report and what it says about the current state of the music streaming market and the labels’ efforts to keep the good times rolling.

More MIDiA Analyst Tatiana Cirisano has an interesting take on how and why the interests of artists and hosting platforms are converging around “non-rights-centered” monetization strategies, like emphasizing podcasts and video.

There Oughtta Be a Law On Tuesday, the U.K.’s music industry organization UK Music issued a report touting the strength of the British music business but acknowledging the challenges posed by AI. On Wednesday, the songwriters organization, Ivors Academy, offered its own perspective, issuing a “that’s nice, but…” response to the report. “We are working with industry partners to ensure transparency in AI-generated music and robust protections against the unauthorised use of songwriters’ work. If industry solutions on AI fall short, we are prepared to call for legislative action [sic],” its statement read. It also wants to see changes to the streaming business UK Music cited. “Publishers are important partners for songwriters and composers, yet their ability to secure fair revenues is often constrained. Record labels typically negotiate with digital service providers first, leaving publishers to compete for a smaller share of revenue allocated to the song. This imbalance must be corrected to ensure digital revenues are distributed more fairly.”

Another AI Case Tossed U.S. District Court Judge Jed S. Rakoff on Friday dismissed most of The Intercept’s AI copyright infringement suit against Microsoft and OpenAI. The case against Microsoft was dismissed in full, with prejudice. The case against OpenAI was narrowed to the § 1202(b)(1) claim of removing copyright management information. Order is here; full opinion was not yet available.